Since 2016, researchers at Project 39A have published a staggering amount of information relating to the death penalty in contemporary India. Among several troubling developments, their latest annual report found 561 prisoners on death row at the end of 2023 - the highest number since 2004 . The report attributes this swelling figure to two factors: the increasing readiness of lower courts to pass death sentences and the longer processing time for higher courts to dispose of cases. As this research has also consistently demonstrated, those condemned to death are overwhelmingly composed of the poor and those from marginalized backgrounds.

While legal scholars and human rights organizations continue to shed light on what is being described as “ India’s burgeoning death penalty crisis ”, h istorians have hitherto paid scant attention to the historical forces informing the evolution of this punishment over time. In an article recently published in Law and History Review, I examined material relating to capital punishment found in archival documents, Constituent Assembly debates, newspaper records, Supreme Court judgments and Law Commissions. The article was framed around a specific question: How did an institution so intimately bound up with colonial state violence not only survive decolonization, but become legible within a new political landscape defined by the vocabularies of constitutional democracy and popular sovereignty?

The article begins with the history of capital punishment at the end of empire. Most striking here is the sheer scale of executions. Between 1925 and 1944, the colonial state recorded an average of 577 executions a year in India. For context, the government in England and Wales executed a sum total of 632 convicts between 1900 and 1949. [1] Also noteworthy, the rate of executions in India was growing decade on decade under British rule. Colonial justice became more bloody as independence neared, not less.

As executions numbers rose, a recognizable abolition movement emerged during the interwar period. Newspapers and law journals printed pro-abolition articles, penal reform organizations were established and Indian politicians tabled resolutions to abolish the death penalty in legislative assemblies. Predictably, calls to temper state violence were afforded short shrift by the colonial administration. While the movement struggled to make headway with the colonial government, signs of progress were evident elsewhere. In a set of developments ripe for further scholarly inquiry, several of the semi-autonomous Princely States dotted across British India had dramatically reduced the use of the death penalty by the 1940s. Cochin State, a coastal state in southern India, ended capital punishment in 1944.

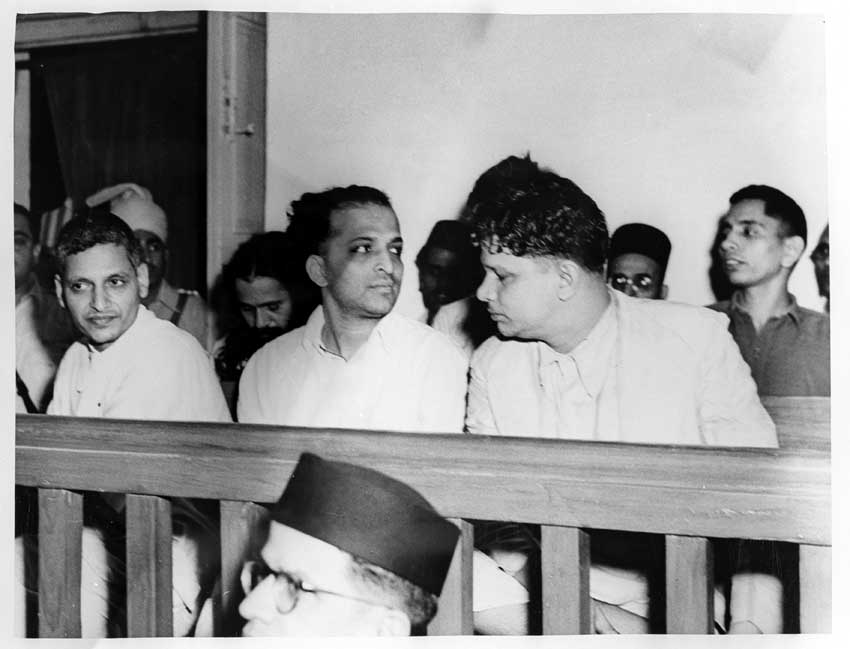

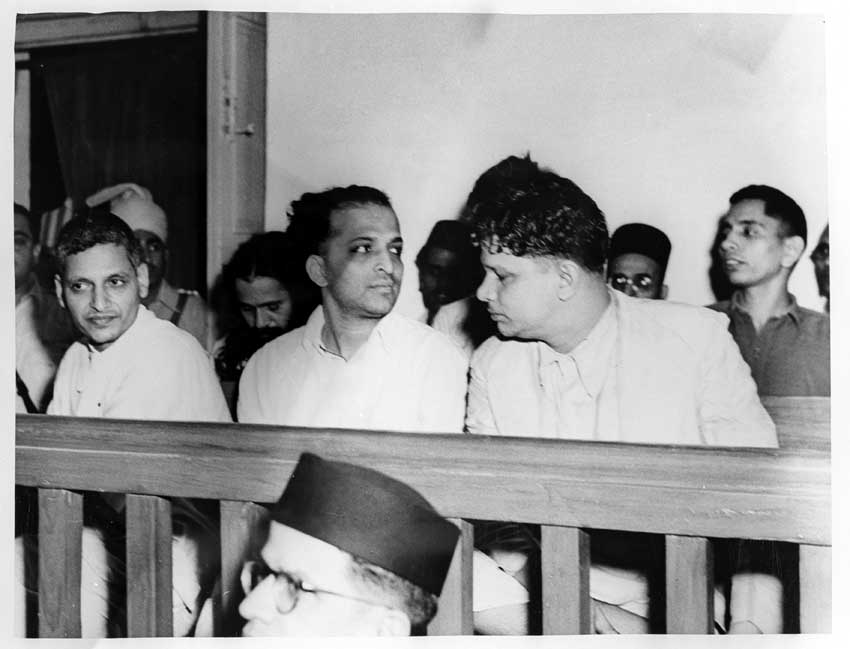

Though abolition was supported by some of the most important nationalist leaders of the time, the tumultuous conditions that accompanied independence did not lend themselves to progressive penal reform. The horrors of partition, war in Kashmir, and the violent annexation of Hyderabad led many to conclude that the death penalty should not yet be relinquished. A notable factor was the assassination of M.K. Gandhi. In one of history's dark ironies, the murder of the world’s most famous proponent of nonviolence was quickly leveraged by Indian retentionists as powerful evidence supporting capital punishment. As the powerful Congress politician C. Rajagopalachari argued, “I cannot think of a stronger case for the infliction of death … [the assassin] stabbed the heart of India itself.” [2]

Image: The trial of those accused of the murder of M.K. Gandhi, 1948. Photo source: Flickr, licensed under Creative Commons CC BY 2.0 DEED.

If abolitionist efforts faltered, independence brought significant changes to the death penalty. Amendments to the code of criminal procedure and a more merciful postcolonial executive resulted in a sharp decline in executions. In response to persistent abolitionist efforts, the government ordered the first major study of capital punishment in 1962 through the establishment of a Law Commission to examine the question. After consultation with legal professions, local governments, and the public, the Commission published its findings in 1967, recommending retention. The report stated that India had not reached the appropriate “stage” for abolition and pointed to low levels of education and India’s diversity and size as evidence. While maintaining a paternalist logic, the report did not simply recycle old colonial arguments. As the authors also explained, the Indian death penalty was supported by the “majority of citizens” which made the punishment an effective “expression of public indignation at a shocking crime.” [3] The death penalty was now legitimated through a language consonant with ideas of popular sovereignty.

Shortly after the Law Commission published its findings, the constitutionality of the death penalty was considered by the Supreme Court in a host of important cases between 1973 and 1983. [4] On one hand, the Court sought to ensure that death was firmly understood as the exception in the punishment of murder, characterized by the introduction of the “rarest of the rare” standard proposed in Bachan Singh vs State of Punjab (1980). [5] On the other hand, as the death penalty was retained, judges consistently returned to (and strengthened) the link between popular outrage and the validity of the capital punishment. This process culminated with Machhi Singh vs State of Punjab (1983), in which the Court explained the “rarest of the rare” through reference to crimes in which the “collective conscience is so shocked.” [6] The discursive shift has proven incredibly consequential. In a 2015 study published by the Asian Centre for Human Rights noted that some variants of this phrase have become a signal feature of death sentences ever since.

The remaking of the death penalty as state violence legitimated by abstract notions of the popular will has contributed to the death penalty’s subsequent durability in India, as well its expansion in recent times. As various scholars have noted, from the 1980s Indian politics became increasingly shaped by the rising force of Hindu nationalism. In this context, populist leaders quickly grasped the symbolic power of the death penalty. [7] How better to demonstrate your ability to police and protect an exclusivist idea of the people and nation than by proclaiming your willingness to kill in its name? Death penalty talk developed into a feature of election campaigning, political manifestoes promised to make more crimes punishable with death and opposition leaders demanded the execution of infamous criminals during blood-curdling political speeches. The number of capital offenses steadily grew during this period. [8]

The relationship between the death penalty and majoritarian Hindu nationalism continues in lockstep to this present day. In December 2023, the Indian Parliament passed three new bills which promise to completely overhaul the system of criminal justice in India. [9] In scrubbing the statute books of nineteenth-century penal codes, the government has celebrated these changes as major landmarks in ongoing efforts to decolonize India’s legal system. In the official press release, the bills were pertinently positioned squarely within the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) wider nationalist political project. As the release explained: “ Be it Ram temple, Article 370, Triple Talaq or women reservation… we do what we say . ” [10] The content of these laws, and especially the enlargement of police powers, has provoked serious concern from legal scholars . Among its proposals, the new laws will also expand the number of offenses punishable by death . Whether the death penalty deserves such prominence in codes touted for their newly acquired Indian “ soul ” does not appear to have been considered worthy of debate. These laws received Parliamentary assent during a session in which over a hundred opposition members were suspended from Parliament. The most radical changes to India’s system of criminal justice for over a century, therefore, were agreed upon in front of “opposition benches almost empty.” And yet if these new bills result in more death sentences and more executions, they will serve less as a break from the bloody days of colonial rule, but rather simply exacerbate the structural violence that already marks the institution of capital punishment in postcolonial India.

This article draws upon findings published in Alastair McClure, 'Killing in the Name Of? Capital Punishment in Colonial and Postcolonial India' (2023) Law and History Review 41, 365-385.

| Alastair McClure is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Hong Kong. His forthcoming book is titled Trials of Sovereignty: Mercy, Violence and the Making of Criminal Law in British India, 1857-1922 and will be published by Cambridge University Press in November 2024. |

[1] Victor Bailey, “The Shadow of the Gallows: The Death Penalty and the British Labour Government, 1945-51”, Law and History Review, 18:2 (200), 306.

[2] Cited in Alastair McClure, “Killing in the Name of? Capital Punishment in Colonial and Postcolonial India”, Law and History Review, 41 (2023) 373.

[5] Bachan Singh vs. State of Punjab, AIR 1980 SC 898.

[6] Machhi Singh and Others vs State of Punjab, 1983, 957, 1983 SCR (3).

[7] Thomas Blom Hansen, The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu Nationalism in Modern India, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 8.

[8] In the 1980s, the death penalty was included in three new Acts, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1985; Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987; Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. For the crimes punishable by death in India see here.

[9] These bills were the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita and the Bharatiya Sakshya Act. They will replace the Indian Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure, and the Indian Evidence Act.

[10] The revocation of Article 370 in the Indian Constitution in 2019 ended Kashmir’s special constitutional status which afforded greater autonomy to the only Muslim-majority state in India. While triple talaq has been the site of longstanding debate within the Indian feminist movement, the attention given to this issue by Hindu nationalist political parties has been questioned by legal scholars, described by Flavia Agnes as a “minority-bashing exercise”. Finally, the recent construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, believed by some to be the birthplace of Ram, was built on top of the sixteenth-century Babri Masjid. The mosque was demolished by Hindu nationalist activists in 1992, resulting in large-scale communal riots and violence.

Photo credit for preview image of the flag of India: Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 DEED.